„The dative is the death of the genitive“, the book where Germans make fun of their own language

Is it possible to combine studying and careful attention to the proper use of the language whilst having fun?

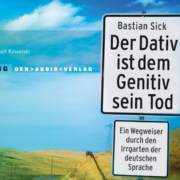

But above all: is it possible to do so with the German language, generally considered one of the most difficult to learn due to its lexicon and rigid grammar that recalls the Latin one? The innovative German grammar booklet „Der Dativ ist dem Genitiv Sein Tod“ (translated „The Dative is the death of the Genitive“), made up of 6 volumes published by Kiepenheuer & Witsch between 2004 to 2014, seems to have been able to do that perfectly, given that for the first time ever a language manual has managed to become an international bestseller with over 3 million copies sold.

Sebastian Sick, The dative is the death of the genitive

The author of this achievement is Bastian Sick, curator of the linguistic column Zwiebelfisch on Spiegel Online: the German term Zwiebelfish indicates those letter of a text that by mistake are reported in a different character compared to the others; Sick chose the term Zwiebelfisch as a title for his column as a metaphor of the German phenomenon of using words and expressions that would formally be incorrect. Journalist, entertainer, but especially a humanist specialized in history and romance philosophy, Sick began his career as a translator and interpreter: his passion for German language and grammar has allowed him to achieve a fine awareness of the language that is hard to find amongst professionals of the academic world and schooling staff. The title of Sick’s work “The dative is the death of the genitive” alludes to the grammatically incorrect replacing of the genitive with the dative in a lot of current German expressions. The same expression “Der Dativ ist dem Genitiv sein Tod” is grammatically incorrect, yet spread widely following the publication of the work. The 6 volume collection is a compilation of the articles published in Sick’s coloumn Zwiebelfisch.

The method

The case studies selected by Sebastian Sick aren’t tailored expressions, literary texts or lists of rules to learn by heart, but sentences that derive directly from conversations amongst native speakers, road signs, advertisements or newspapers. Sick deals with great humor certain grammatical, spelling and pronunciation cases that are common in modern day spoken and written German. Everyday life becomes the occasion through which even those whose first language is German have a chance to reflect and talk about it with friends and acquaintances without having to resort to dusty toms stored in the library. At the same time Sick’s approach is also good for those who are new to the German language, but wish to know the nuances they often miss during frontal lessons. Sick’s work is one that aims to convey not only the rules for a good use of the language, but also the pragmatic, whose traditional study is often difficult to understand even within an academic environment. At a time where we are all coming to the terms with having the best results in the shortest amount of time, mistakes are demonized to the point of making us forget the universal truth that lies within the saying “one learns through mistakes”. Highlighting mistakes and analyzing them with the right lightness and irony, without falling into strict academic rigorousness, silencing the shame and fear of making another mistake, allowing you to better accommodate the corrections and learn the language effectively.

The opinion of the readers

Precisely due to its innovative features, “Der Dativ ist dem Genitiv sein Tod” hasn’t been welcomed warmly by everyone. Some appreciated Sick’s style and humor to the point of having integrated his manuals within the bibliography to prepare for German exams, others have instead condemned him for his method of analysis. Others have even spoken against it becoming an school text, as deemed not to be fit for students. As for any language manual there will never be a universally positive judgment, however one must recognize certain unique aspects of Sick’s work. In the first place he has a real talent in getting the reader’s attention on the topic, considering that it is not of the most approachable. In the second place is his focus on the modern day use of the language, which is ever more important to foreigners arriving to Germany right now. There will always be the fans of the “purist” language, that spend their time correcting the common use of new grammatically incorrect expressions, however given that every spoken language has a life of its own maybe it is time one accepts Sick’s lightness and irony: debating about mistakes, neologisms, of the most uncommon expressions can contribute in helping speakers to become more aware and conscious of the language’s mobility and variations.

In the meantime, if you wish to test your knowledge of the language, you can try to answer the following quiz available on Sebastian Sick’s private page!

Are you new to the language or have studied a bit of it and wish to perfect it? Take a look at the German courses that Berlino Schule organizes in Berlin!